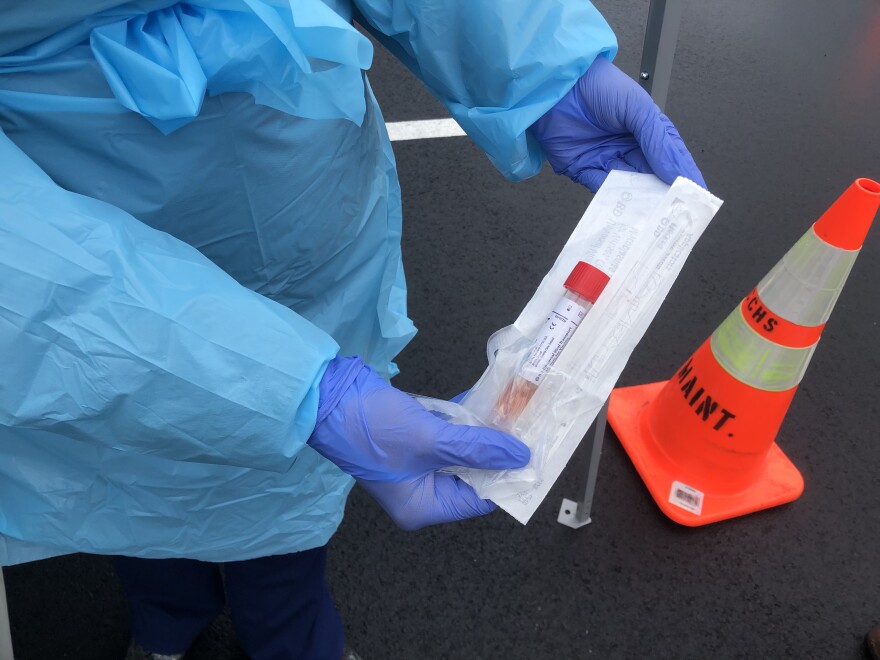

The rollout of testing for the new coronavirus disease in the U.S. has been criticized as too slow. Whether the First State has enough tests remains an open question.

Roughly a week after Delaware’s public health lab in Smyrna was approved to run tests for COVID-19, state officials said the lab had ramped up to processing around 40 tests per day — but could run up to 100 per day if needed.

At this point in Delaware, residents must be experiencing both a fever and either a cough or shortness of breath to qualify for testing.

The commercial laboratory chain LabCorp can run tests on specimens collected by medical providers, such as family doctors.

State officials have maintained that with the combined force of commercial labs and the state public health lab, Delaware has the capacity to meet its current COVID-19 testing needs.

But state public health director Dr. Karyl Rattay admitted at a press conference Wednesday there is “prioritization” in which symptomatic people should be tested.

“It is very important to us that those who are most ill— like those who are hospitalized— are tested, as well as those who are in the highest-risk groups, like those over age 60 as well as those with chronic underlying conditions,” she said. “Also, as it’s so important that we protect our first responders and healthcare providers, any of those individuals with symptoms we want tested right away.”

Roughly 760 specimens in total were sent to commercial labs from drive-through events held by ChristianaCare and Beebe Healthcare in Delaware last week.

But Rattay says it is hard even for her division to track the total number of tests being run in Delaware.

“We are trying very hard to keep track of the negative tests, but that has become more challenging as the data collection system is not fully built and quite frankly there are about 15 different laboratories that are doing these tests,” she said. “So we are working on that, but we don’t have a total number at this point that are being tested.”

The time it takes for someone who is tested for the virus to learn whether they have it also seems to vary.

Rattay says the state’s public health laboratory can produce results within 24 hours. LabCorp says its tests take three to four days from the pickup of the specimen to release of the test result— a duration Rattay says is expected to decrease in the coming days and weeks.

ChristianaCare said results of its drive-through swabbing event Friday, which utilized an unspecified out-of-state commercial lab for testing the samples, would be available in two to five days. Beebe said participants in its Saturday drive-through event, which used LabCorp, could expect results within seven days.

Gov. John Carney signaled at Wednesday’s press event that the system of testing in Delaware could change.

“We’re working with the hospitals to develop a statewide testing plan that’s being stood up this week and coordinated across all three counties,” Carney said. “That testing plan will give us a better idea of where we stand in our effort to, as they say, ‘flatten the curve.’”

ChristianaCare currently has no plans for another drive-through testing event — but has launched a Provider Referral Center where symptomatic people with prescriptions and appointments can have specimens collected. Those will go to an out-of-state commercial lab for testing.

“Beebe is working on creative solutions to care for patients on an outpatient basis like last Saturday’s mobile screening event,” said Marcy Jack, chief quality and safety officer at Beebe Healthcare, in a statement. “We are working with and sharing these innovative ideas with the State of Delaware and other healthcare providers to enable expanded access across our community for management of patients with non-emergent symptoms of COVID-19.”

Delaware State University Professor Donna A. Patterson, who teaches about global health and epidemics, praises the drive-through events as effective at helping the state establish a baseline of testing.

“We have done fairly wide testing for this state,” she said. “There are a lot of places still trying to get the number of tests that we’ve done in this state. So I think that’s been kind of an amazing collaboration both with the government [and] … some of the hospital chains.”

Jennifer Horney, founding director and professor in the University of Delaware’s epidemiology program, expressed confidence in Delaware’s testing infrastructure.

“I believe that we are close to having the capacity that we need to test everyone with symptoms and everyone who may be in a vulnerable population group that has a reasonable belief that they’ve been exposed,” she said. “We've maybe solved the supply logistics side of this and now we have more of a communication challenge.”

Horney says testing can only identify the tip of the iceberg — but that significantly expanding testing could bring the challenges of additional false positives and negatives.

“A false positive would use up public health resources during a time of scarcity in terms of isolating that person and investigating their contacts,” she said. “But then on the other hand if we identify someone as a false negative, maybe they feel, OK, I’m negative, I can go out.”

Medical providers can collect specimens and send them to either LabCorp or the state public health lab. People with symptoms but no medical provider are advised to call the Division of Public Health.

Public health experts have asked people experiencing symptoms of the virus to only go to the emergency room if their symptoms are severe or life-threatening.