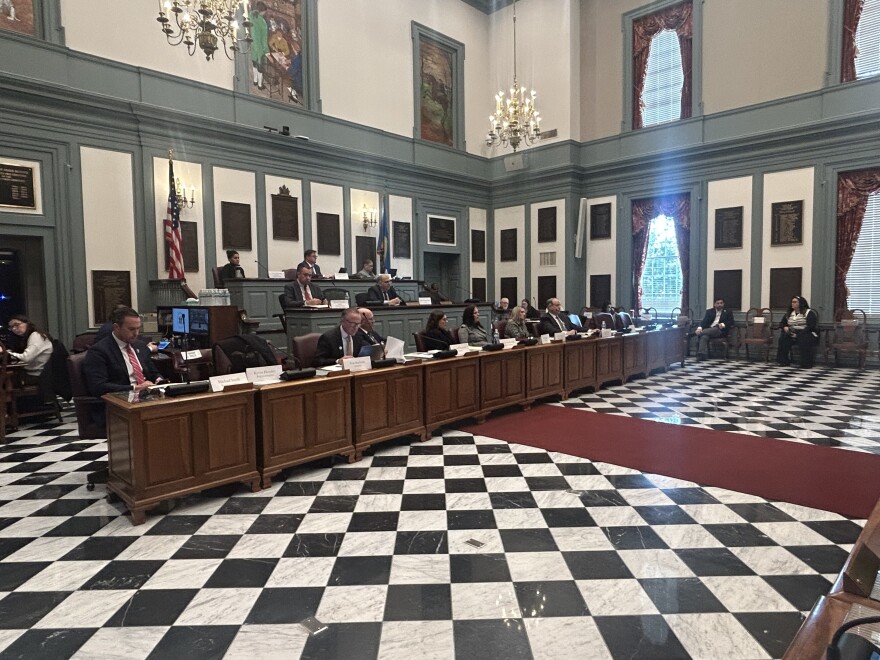

State lawmakers discussed education funding reform with school district representatives at their final property reassessment hearing in Dover Monday.

About 29% of public education revenue comes from local property taxes, according to the Public Education Funding Commission, and local funds can be leveraged to match state-authorized programs.

But this creates inequities for some districts with smaller tax bases and lower property values. Those districts often can’t match state contributions, denying students access to programs or services higher-wealth districts can provide.

Delmar School District’s residential property values totaled about $38 million in 2020 using outdated values. In comparison, Appoquinimink values totaled more than $2 billion and Cape Henlopen totaled about $1.2 billion.

In practice, individual property owners in districts like Delmar have to contribute more to offer the same programs and resources, according to its Chief Operating Officer Monet Smith.

“If Delmar, for example, needs to raise $1,000, it would be like asking five people to all contribute 200 bucks,” Smith said. “However, if a district like Indian River or Cape Henlopen needed to raise $1,000, it would be more like asking 40 people to contribute $25.”

Smith said this is something localities can’t control. And because property reassessment increased disproportionately for lower-value homes, she said lawmakers need to update Delaware’s equalization rate, which was frozen in 2009. Equalization offers resources and materials to lower-income school districts to even out the educational playing field.

“This system has forced poor communities to overtax themselves to provide something close to the same level of service as wealthier districts,” Delaware State Education Association’s Director of Legislative and Political Strategy Taylor Hawk said.

Hawk explained it’s more difficult for districts with lower wealth to raise funds for their schools. She said that difference is not a result of mismanagement but a problematic system powered by “unequal taxing and broken equalization.”

“We can't design a fair school funding system without reliable property valuations,” Hawk said. “If we hope to allocate resources based on a district's true tax base, the underlying numbers must be accurate.”

School district officials challenge referendum system

Delaware went four decades without property value reassessments, meaning schools rely on outdated values despite ballooning costs, according to Hawk.

She said Delaware’s reliance on the referendum system is another issue that affects districts with less property value, “where residents are already overtaxed.”

Hawk called referenda one of the “most restrictive revenue-raising processes in the nation.”

“That in turn leads to discontent and mistrust, which makes voters even less likely to approve the funding increases those districts desperately need to meet the standards our state sets for them,” she said. “These issues of funding and performance are deeply interconnected, and we cannot solve one without addressing the other.”

The DSEA wants long-term solutions, Hawk said, not piecemeal funding fixes.

Sen. Bryan Townsend said the General Assembly will have to come up with tangible solutions in the upcoming legislative session, which starts Jan. 14.

“One of the main challenges we've seen from constituents is that people want to have a vote on tax increases,” Townsend said. “... But I don't think what they fully realize, what a lot of legislators don't fully realize, is Delaware’s system is increasingly antiquated, increasingly broken, and there's a better way that doesn't involve taking away their right to approve major tax increases.”

Townsend said Pennsylvania’s model only requires referendums for major operational and capital increases, not basic operating increases.

Reassessment concerns

Legislators have already started considering future reassessments, which are now set to occur every five years.

And State Rep. Cyndie Romer said she’s worried about the reliability of data collection on property values.

“I am not very confident that we're getting closer to better assessments,” Romer said. “... If we're not getting these assessment values correct in seven months when the next set of bills come out, we're going to be looking at additional problems.”

Townsend agreed, saying he wants the General Assembly to ensure transparency, especially for commercial property valuations.

“We need to ensure the public's much more aware of the timetables and the appeal avenues in case their homes or businesses are not assessed correctly,” Townsend said. “... I particularly think, as we head into another tax year for July 1 2026 there will be new structures in place, like the split rates were only authorized for one year. So whether we reauthorize that or go to a different model, we need to be mindful of the fact that this is going to come up.”

Townsend added the General Assembly will have to set the counties up for success by providing more accurate data, particularly for high-value commercial properties that saw discrepancies.

Major votes to come from the PEFC, Redding Consortium

Committee members proposed potential solutions in their discussions, largely turning to the impending Public Education Funding Committee funding model and the Redding Consortium redistricting decision.

The PEFC plans to send its final model to lawmakers by April, and the Redding Consortium votes on redistricting Tuesday. Both proposals require approval from the General Assembly to go into effect.

State Rep. Mike Smith asked if district consolidation – despite its expected high cost – might improve district wealth disparities.

“There's three options to consolidate just one portion of one county, and that would change the tax rate and everything for everybody,” Smith said.

District officials also suggested updating the state’s equalization formula, which the PEFC is currently working on. The PEFC’s model in the works accounts for equalization based on student needs for low-income and multilingual students but does not currently account for district wealth.

The group meets next Jan. 26 to go over equalization processes.

State Sen. Tizzy Lockman is a member of the Redding Consortium. She asked district representatives what lawmakers should keep in mind when considering policy to reduce resident’s burden and what effect that might have on district revenue.

“Notwithstanding concerns about valuation, this really drives home the fact that we were going to see what feels like the bearing of an unfair burden on households who seem least able to absorb it,” Lockman said.

Townsend said Delaware’s funding mechanisms do a disservice to students and families, and they remain largely uninformed, calling for more transparency in the decisionmaking process.

Residential property owners have the option of entering a payment plan for this year’s property tax bill. Non-residential owners do not have a payment plan option currently.

Townsend encouraged property owners to reach out to county and school district officials if they have questions or concerns about their taxes.