Dover International Speedway hosts its spring NASCAR weekend this week.

But this year is a bit different. 2019 marks 50 years of NASCAR racing at the Monster Mile.

Since its debut in 1969, the track seen its share of highs and lows, largely mirroring NASCAR’s trajectory over the years.

This week, contributor Larry Nagengast charts the track’s history and takes a peek at what lies ahead.

Denis McGlynn remembers the early days of Dover Downs. Fresh out of the Air Force, he arrived in May 1972, hired to handle publicity for the 3-year-old horse and auto racing track.

“It was pretty much a ghost-town atmosphere,” he says. “We had 22,000 seats and we struggled to fill them.”

Harness racing, not stock cars, was the main driver then. “Trying to sell a southern sport in a northern market was a pretty big challenge,” says McGlynn, now the president and CEO of Dover Motorsports Inc.

Seven years later, with Delaware and most of the Northeast snowed in on a February weekend, television sports fans tuned into the Daytona 500 and saw NASCAR drivers Cale Yarborough and Donny Allison crash into each other on the final lap, then engage in a memorable fistfight in the infield after Richard Petty slipped past them for the win.

“It was a perfect storm for us, in a good way,” McGlynn says. Interest in NASCAR started to soar, and Dover began 16 years of grandstand expansion.

Interest would peak in 2001 and 2002 when crowds estimated at 135,000 would pack the Dover grandstands on two race weekends.

Those days are but a fond memory now for McGlynn, but, as the track, now known as Dover International Speedway, marks its 50th anniversary of racing, it’s a time to reminisce about past glories and look hopefully toward the future.

The celebration begins this weekend, with Sunday’s Monster Energy NASCAR Cup Series race being the 99th in the track’s storied history. It will conclude the weekend of Oct. 4-6, highlighted by race number 100, part of the playoff series that wraps up the NASCAR season.

Bob Farrell will be at Dover for both race weekends this year, just as he and his wife Dottie have been almost every year since 1992. “Row 31, on the first turn, you can see the entire track from there. Anything that happens, you can see it,” the 73-year-old Milford resident says.

Farrell also remembers the very first NASCAR race at Dover. Then an airman stationed at Dover Air Force Base, he was one of the 10,509 fans to see Richard Petty take the checkered flag with a six-lap win over Sonny Hutchins in the Mason-Dixon 300 on July 6, 1969.

Jeff Rollins, the son of Dover Downs cofounder John Rollins, doesn’t recall whether he was at the first race. After all, he was only 4 years old at the time. His earliest memory of the track, he says, was “sleeping in the back of Dad’s Lincoln in the tunnel that ran underneath the start-finish line.”

Dover Downs’ origins, Jeff Rollins says, could be traced as far back as 1949, when his Georgia-born father owned a Ford dealership in Lewes and sold some dump trucks to Georgetown construction magnate and auto racing fan Mel Joseph. From that sale, John Rollins and Joseph became close friends.

Fast-forward to 1967, when David P. Buckson, a prominent Kent County politician and horseracing enthusiast, approached Rollins and Buckson with a plan to build a racing complex on 200 acres of farmland on the east side of the Du Pont Highway in Dover. The blend was ideal: Buckson knew horses; Joseph had the auto racing contacts and could handle the construction, and Rollins provided the financial expertise. Nor were they lacking in political savvy; Rollins and Buckson, both Republicans, won elections to serve as Delaware’s lieutenant governor, Rollins in 1952 and Buckson four years later.

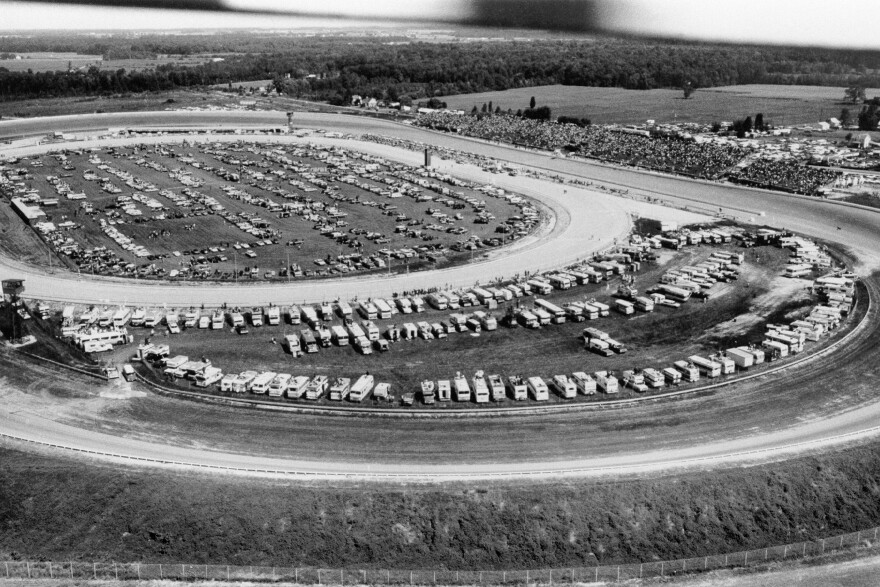

A 5/8-mile horseracing track was set inside the one-mile banked auto racing oval now known nationwide as the Monster Mile. The first horse races were held at the track in March 1969. Auto racing would follow four months later.

“Mel Joseph wanted to make it something special,” says retired NASCAR driver Bobby Allison, who posted seven wins at Dover between 1971 and 1983. “The banking [9 degrees on the straightaways and 24 degrees on the turns] and the approaches to the turns made it difficult. It was very demanding physically and a lot of the other guys complained.”

According to McGlynn, Buckson was most often at the track when the horses were running, and Joseph was a significant presence during NASCAR events, but it was Rollins who kept the closest eye on the business operations. “John was the everyday guy. He’d call me three times a day during the week and twice on weekends,” McGlynn says.

Thoroughbred racing didn’t last long at Dover, ending in 1974, McGlynn says, thanks to the combination of high expenses, the shortage of quality horses and the opening of new tracks in major metropolitan areas, like The Meadowlands outside New York City.

Harness racing had its heyday in the 1970s. At the time, McGlynn recalls, Dover was the only track in the region with Sunday racing, and it wasn’t unusual to see 30 to 40 buses from as far away as New York in the parking lots on snowy Sundays in January and February. In time, however, other states authorized Sunday racing and competing tracks, rather than rotating their racing meets, began overlapping their seasons. With the rise of simulcasting and off-track betting, attendance at harness tracks began to decline, but subsidies through the growth of the gaming industry, in Delaware and other states as well, have kept the sport alive.

Meanwhile, fueled by the interested generated from the 1979 Daytona 500, NASCAR and Dover enjoyed steady growth through the 1980s and 1990s, and peaking in 2001 and 2002.

McGlynn especially remembers the 2001 fall race weekend, held just a week and a half after the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks. “It was tension-filled, emotion-filled,” with plenty of pre-race and race-day security collaboration with the FBI, the Secret Service and other government agencies, he recalls. Race sponsor MBNA and Dover Downs partnered to buy 135,000 American flags and hand them out to fans as they entered the track.

“They were chanting ‘USA, USA.’ They were doing the wave, pounding on the grandstand. It was electrifying,” he says. “To be able to pull it off, that was a great thing.”

The decade would be tough for NASCAR, with iconic driver Dale Earnhardt killed in a crash at Daytona in February 2001 and many of its top drivers retiring in the following years. But hefty cable television contracts were transforming NASCAR’s revenue model, so it became less dependent on attendance at its tracks.

Buoyed by strong Delaware corporate sponsors like the DuPont Co. and MBNA (followed by its successor, Bank of America), Dover would continue to thrive until the recession of 2008.

Then, as businesses retrenched, companies slashed their marketing budgets. Dover could no longer count on the revenue from the tickets corporations would buy for their employees and clients, and many of the sport’s blue-collar fans were now unemployed. “When you take 22,000 out of the grandstand all at once, it’s hard to replace them two-by-two-by-two, especially when the people who were buying two by two weren’t working anymore,” McGlynn says. “It was the perfect storm in the opposite direction.”

In the past decade, Dover has steadily transformed itself.

About 50,000 grandstand seats have been removed because, McGlynn says, “you don’t want to have 50,000 empty seats [shown on telecasts] because it’s not going to look good.”

Venues with smaller seating capacities are the trend across the sports and entertainment world, notes Mike Tatoian, president and CEO of Dover International Speedway. “They’re becoming more intimate. Everyone is ‘right-sizing.’” He believes the days of building facilities with 100,000 to 150,000 seats may well be a thing of the past, but acknowledges that “nobody knows what will happen in 50 years.”

While removing seats, Tatoian says, “we had to consider where they were located, and what we could do with the space we created.” So Dover added amenities, including a Fan Zone that features an array of activities – interactive displays, games, music, and exhibits by racing sponsors. Also new this year – Delaware –themed food offerings prepared by SoDel Concepts, the Rehoboth-based restaurant group.

In its pursuit of new revenue sources, the track moved in an entirely different direction in 2012, hosting the first Firefly Music Festival in The Woodlands, the huge wooded and grassy area almost entirely on the east of Route 1. Now in its eighth year, Firefly’s three days of music draws 90,000 to 95,000 fans.

As for the races, McGlynn says he now expects attendance to be “in the mid-40s,” though it could be higher this year because of the anniversary celebration. In other words, attendance for two weekends of the track’s signature events draws fewer people than a 72-hour rock concert.

“If we could do better, I’d be very happy, but that’s the way the industry is trending,” McGlynn says. “We’re not better, no worse. The stragglers have been falling off since 2008. Everybody seems to be down to a core audience.”

A renewed emphasis on customer service has kept those core fans loyal. “My wife and I have been to nine tracks, and Dover is the nicest by far” says Bill Burke of North Providence, Rhode Island, who has been traveling in his RV to Dover twice a year for the past decade. “It’s a very well-run race. People are very considerate. Great emergency services, great food, it’s clean and safe. People in the ticket office are attentive to every problem. And when we got stuck, they even towed us out of the mud.”

While attendance may be shrinking to that core audience, there are few thoughts of gloom and doom in Dover.

Television contracts have helped reduce the reliance on paying customers. The search for ways to attract the next generation of fans, and to make the venue more compelling than hundreds of other media and entertainment options, is a challenge not only for NASCAR but for the entire sports industry, McGlynn and Tatoian say. And who knows what the future will bring. Autonomous vehicles? Fans using augmented reality gear to virtually put themselves in the driver’s seat?

“Everybody knows it’s not like it was 10 years ago,” says Jeff Rollins, who serves on the Dover Motorsports board of directors. “But if you compare it to 20 years ago, this is still a pretty nice business.”

And McGlynn believes a new generation of fans will stay … provided he can get them to the track.

“Some people say it’s just a bunch of cars running around a track on television,” he says, “but when you stand out there, and cars go by at 140 miles per hour and they vibrate your bones, suck the air out of your lungs and make you dizzy and you want to fall down, well, that’s a whole different experience.”