Making a move that would have seemed counterintuitive two decades ago, in early 2018 Bob and Anne Daly left behind the hustle and bustle of booming Middletown and headed north, seeking serenity in Brandywine Hundred.

The retired DuPonters found a house on a short street off Baynard Boulevard that dead-ends, appropriately enough, into a cemetery, across the street from a onetime church that hadn’t been used for half a century. Their real estate agent told them that three exterior walls of their new home dated to 1683. Other than that, they had little idea of what they were getting into.

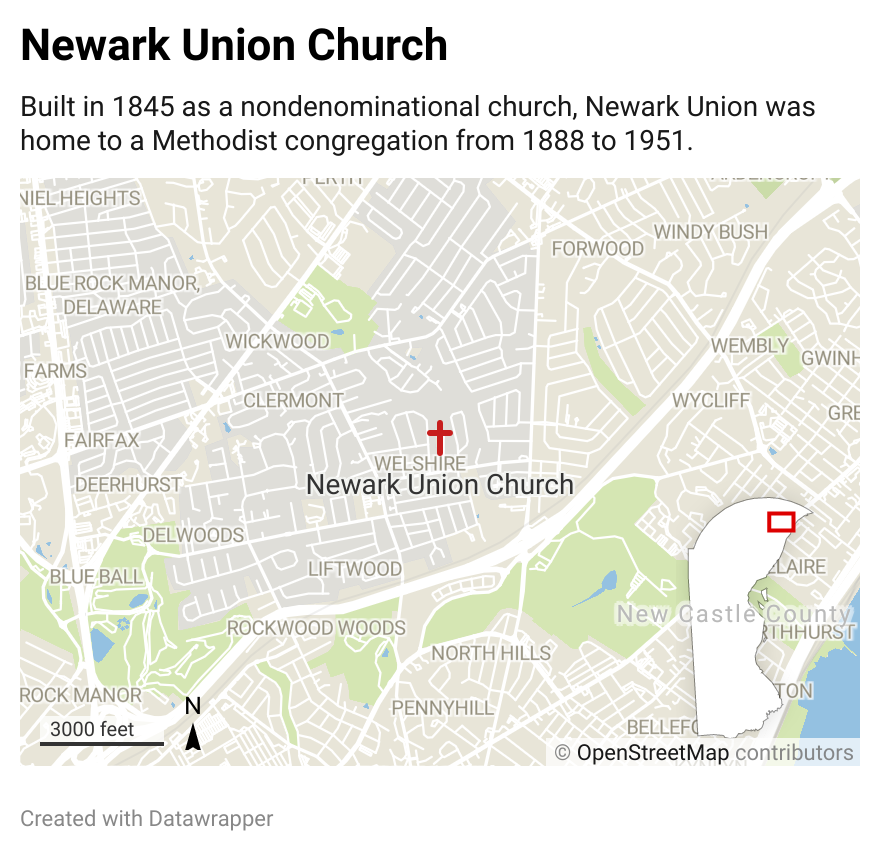

In the last three years, Bob, a 61-year-old entomologist, and Anne, a 65-year-old chemist, have become historians and preservationists, guiding the effort to restore the Newark Union Church, where thousands of Brandywine Hundred residents worshiped between 1845 and 1970, and researching the lives of those buried in the Newark Union Cemetery, where some of the grave markers are more than 300 years old.

The Dalys “arrived at just the right time,” says Brandywine Hundred historian and preservationist James R. Hanby Sr., some of whose ancestors worshiped at the church and are buried in the cemetery.

As president and treasurer of the nonprofit Newark Union Corporation, the Dalys are trying to transform the church into a combination museum and event venue – a place to exhibit Brandywine Hundred’s history and to host gatherings like memorial services, weddings and community meetings. They had barely started last year when the COVID-19 pandemic put much of their work on hold for about a year.

“I love working with constituents who are earnestly striving to burnish our local heritage,” says New Castle County Councilman John Cartier, whose eastern Brandywine Hundred district includes the church and cemetery grounds. “They’re doing a fantastic job.”

A repurposed church “has all kinds of possibilities,” says Cartier, adding that he would like to host an “inaugural event” there when the work is done.

"I love working with constituents who are earnestly striving to burnish our local heritage. They're doing a fantastic job."New Castle County Councilman John Cartier

But that’s going to take time, since the effort is led by volunteers and up to now has relied on relatively small donations.

The restoration story starts shortly after the Dalys moved into their new home. Soon they met Ray and Jean Weldin, whose ancestors, like Hanby’s, had been buried in the cemetery. Members of the Weldin family have had a role in caring for the church and cemetery for more than two centuries.

“The Weldins came here to do various projects. We met them. They were very nice people, but they were getting older and may have been looking for someone to take over for them,” Bob Daly says. “Every time we saw them, Jean Weldin had a little gift, a historical piece of the church that she would bring over, an old branding iron from the Weldin farm.”

When asked if they would consider taking over, the Dalys promised to think about it.

The clincher came when Jean Weldin brought over the church’s original ledger book, with the first entry on March 8, 1845. “It’s a who’s who of people around here talking about building the church,” Daly says as Cindy Davis, the nonprofit’s secretary, starts reeling off names like Weldin, Forwood, Carr, Wilson, Talley, Day, Beeson, Sharpley and Miller, all easily recognized by anyone familiar with Brandywine Hundred’s major roads and parks.

“That’s how we got involved,” Daly says.

As they immersed themselves in history, one of the first things the Dalys learned was how a site roughly 18 miles from the city of Newark got its name. That goes back to 1682, when William Penn granted 986 acres stretching from Shellpot Creek west to the area now known as Blue Ball on Concord Pike to his Quaker friend, Valentine Hollingsworth, who named the land New Worke. Over time, the spelling was tweaked, to New Work, New Wark and New Warke, eventually evolving into Newark, the same as the college town.

Hollingsworth built his home there and dedicated a half-acre of his land as a Quaker burial ground. After multiple uses and upgrades, the house is where the Dalys now live. Quakers in Brandywine Hundred held their meetings in Hollingsworth’s home. Then, in 1704, they built a small log meetinghouse on the edge of the cemetery grounds. Quakers gradually moved to west of the Brandywine, to Centreville and Kennett Square, Pennsylvania, and the log meetinghouse was eventually taken down. Over time, the cemetery transitioned into a multidenominational burial ground. In 1845, residents raised funds to put up build a stone wall around the graveyard and erect a church, which Lewis Zebley and John Sharpley were paid $800 to build.

The 28- by 40-foot building with stuccoed stone walls resembled many of the farmhouses in the area, according to the registration form for the church’s inclusion on the National Register of Historic Places. Methodists, Presbyterians and Episcopalians were the primary users of the church until 1888, when trustees of the Newark Union Corporation requested entry into the Wilmington Methodist Episcopal Conference, leading to the church’s designation as a Methodist house of worship. In the second half of the 19th century, Methodism had become the dominant religion in the state.

In 1906, the building was renovated and transformed into its current Gothic Revival style, with the main entrance moved to the east side and the three other sides outfitted with tall, Gothic-style lancet windows.

Newark Union remained a Methodist church until 1951, when the congregation moved to Concord Pike and renamed itself as Aldersgate United Methodist Church. From 1957 to 1970 an evangelical congregation used the church, then built a new brick church a few hundred feet away, changing its name from New Ark Union to Shellburne Bible Church. Since then, the 1845 structure has been largely unoccupied, with the Newark Union Corporation taking care of maintenance of both the church and the cemetery.

The Dalys have succeeded the Weldins as the primary officers of the corporation, with Bob serving as president and Anne as treasurer. The board of directors includes members of families like the Hollingsworths and Weldins, who have multigenerational ties to the church and cemetery, as well as residents of nearby neighborhoods, like Davis, whose house in Normandy Manor backs up to the cemetery.

“The corporation has an investment account that maintains the church and cemetery property, but it’s not significant enough to cover repairs and restoration, so we need donations and grants,” Anne Daly says. The corporation received certification early this year as a nonprofit organization, so it is now in a better position to solicit grants, she says.

So far it has received two grants for work on the church – one last year from Preservation Delaware to restore electrical service and $10,000 last month from the Welfare Foundation for exterior work. But the needs are much greater. Current estimates are: $55,000 for exterior repairs and restoration; $60,000 for window restoration; and $19,000 for repairing and painting interior plaster, which is just a fraction of the interor work needed.

With limited funding and volunteer help coming from board members, neighbors and a Daughters of the American Revolution chapter, the restoration project is moving slowly. Interest is continuing to grow; a Facebook page, started in March 2020, already has more than 300 followers.

This year, the work is focusing on the exterior, including replacing the roof, repointing the chimney, repairing soffits and stucco, painting and adding gutters, something the building never had, Bob Daly says.

Contractors with family connections to the church are doing some of the work – an 11th generation Hollingsworth is handling the exterior painting, and a 12th generation Hollingsworth is doing the roofing. “They’re getting paid,” but the relationships make it likely that they’ll do a little more or donate something back to the project, Anne Daly says.

Replacing the seven massive lancet windows, especially replicating the pattern of the glass, will cost $8,000 each, but donations have been pledged to pay for five of them, she says. Restoring two smaller windows adds another $4,000 to the tab.

"If all goes well, we'll finish in 2023. We don't want to be doing this for 10 years. We're not getting any younger."Bob Daly

“This year, if we can get the outside done, it will have been an amazing year,” Bob Daly says.

In the fall, the nonprofit group will continue to seek grants to continue its work on the interior. In addition to the plaster repair and painting, other needs include removing ceiling tiles to once again expose the original beams and repairing and restoring the woodwork, including pews and railings.

Hanby, the historian and preservationist, is encouraged by what he’s seen of the project, especially the increased interest of volunteers. “There’s so much to be done, and they’re not doing it with a lot of money, so you have to do it with your hands. Then you’re invested in it,” he says.

“If all goes well, we’ll finish in 2023,” Bob Daly says. “We don’t want to be doing this for 10 years. We’re not getting any younger.”