During the next two weeks, a new school year will begin for nearly 160,000 students throughout Delaware.

A significant number of those students – especially those among the more than 60,000 who are classified as low-income or English-language learners – will return to their classrooms knowing less than they did when they left in June.

The deficit is caused by a phenomenon – if you can call something that was first identified more than 100 years ago as a phenomenon – called “summer learning loss.”

Low-income students have fallen one and a half years behind their middle-class peers by the time they finish fourth grade, and three years behind by the time they finish eighth grade, and two-thirds of that achievement gap is the result of summer learning loss, says Catherine Lindroth, creator of the Summer Learning Collaborative, a 5-year-old Delaware program that has begun making strides toward reversing that trend.

From its modest start with five locations in 2014, the collaborative has grown to reach 2,700 children in kindergarten through eighth grade this summer at 19 sites, a combination of schools and community centers from Wilmington to Laurel.

The collaborative does pre- and post-testing of all program participants to determine the progress they’ve made. While results for 2018 haven’t been tallied, the figures for the 2,000 participants last summer showed impressive results: 86.5 percent of participants reversed their summer learning loss and 66 percent showed gains in literacy, with average gains of 1.3 months in sight word recognition, 2.3 months in phonics and 7.6 months in vocabulary.

Lindroth began developing the program in the fall of 2013, when she was working in the Delaware office of Teach for America and started getting calls from community centers, asking whether Teach for America corps members might be available to help tutor children in after-school programs so they could get their performance up to grade level. Teachers weren’t available for after-school tutoring, so Lindroth and Laurisa Schutt, then the head of the Delaware TFA office, hit on the idea of a souped-up summer camp and convinced Barclaycard US to award a $10,000 grant to get it started.

“When we got started, I had no idea this problem existed,” Lindroth says. “We started placing teachers in community centers [in the summer] because they were asking for teachers.”

Funded by a combination of corporate and foundation grants, the collaborative delivers its services at a cost of a little more than $400 per child by working with an already established infrastructure of community centers. There’s no fee for participants, other than what they might be paying for community center programming. Lindroth hopes to eventually make collaborative offerings available to children from moderate-income families for a relatively small fee.

The centers – like the Walnut Street YMCA, the Boys & Girls Clubs of Delaware, West End Neighborhood House, Kingswood Community Center, the Latin American Community Center and others – already had summer camp operations. The collaborative builds an academic program that blends into summer camp activities. The participants still get their time in the gym and the swimming pool, and do an assortment of the typical camping arts and crafts, but the collaborative builds in one-on-one reading instruction and two project-based learning activities, one with a science-technology focus, the other featuring arts and music, every day.

The activities are designed to challenge participants’ creativity, to help them learn without feeling that they’re in a school setting. “At the start, they want someone to tell them how to do things, and we say, ‘no, you have to figure it out yourself,’” says Tonya Baines, a program coach at the collaborative’s Shortlidge Academy and Urban Promise sites. “They grow in critical thinking skills and in confidence. Once they get used to it, they’re having so much fun that they want more.”

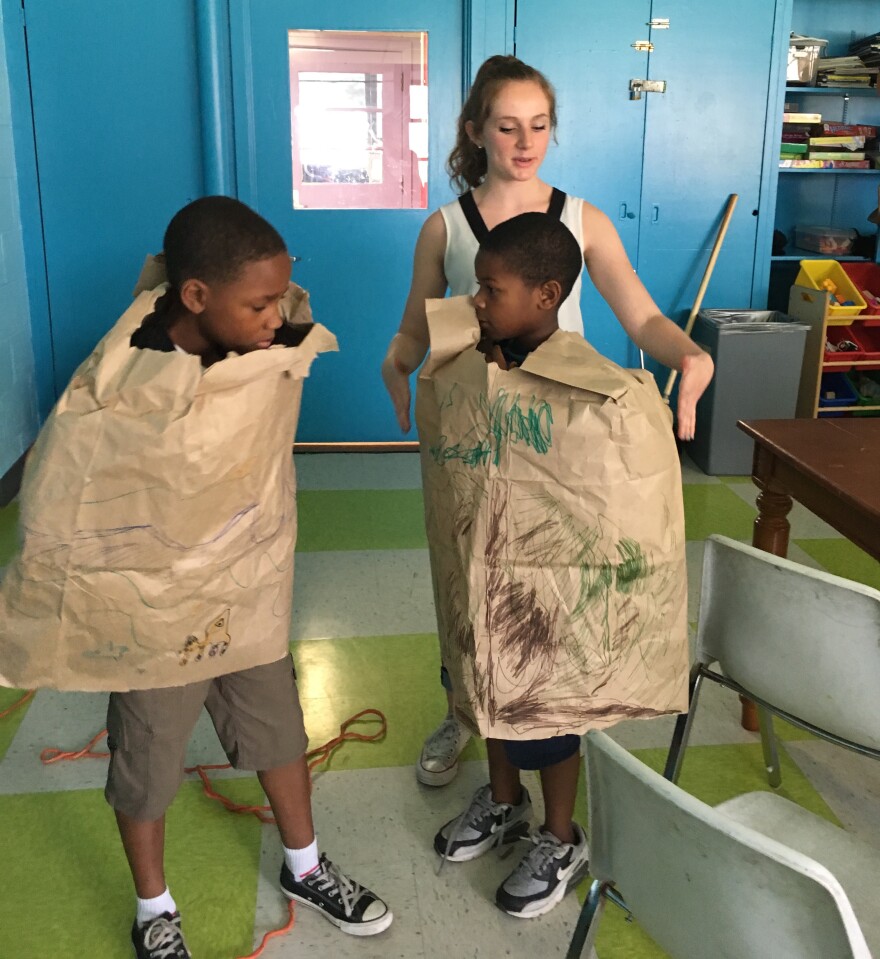

Earlier this month, during a morning session at the Kingswood Community Center in northeast Wilmington, one group of children met with their reading tutors while a second used colored markers to draw on large brown shopping bags to create wearable camouflage characters. In another room, a third group filled a half-dozen glasses with different amounts of water and then tapped on the glasses as they tried to create a musical tune. The week before, they made drums by stretching balloons over a set of cups, said Amy Albright, the collaborative’s program coach at Kingswood and a third-grade teacher at Castle Hills Elementary School in the Colonial School District.

Meanwhile, at Salesianum School, one of five sites for the collaborative’s Tyler’s Camp, a 3-year-old program for middle school students, participants were learning computer coding skills, creating games out of peg boards, marbles and rubber bands, and choreographing dance routines for an end-of-season performance.

“There are no set answers. They’re solving problems with limited supplies and with limited solutions,” says program coach Kelly Bell as she watched campers create a balancing game with the peg board and marbles. “They’re working as a team. They’re having fun. They’re talking about science without saying ‘science,’ and when they get it on their own, it sticks better.”

During the school year, Bell teaches math at Serviam Academy, a private middle school in New Castle for girls from low-income families. Serviam students participated in Tyler’s Camp at Salesianum as part of the school’s extended-year program.

(Tyler’s Camp is named in memory of Tyler Brown, a Salesianum student who was killed in an auto accident in March 2016. His parents are among the program’s financial supporters, Lindroth says.)

A prime reason for the collaborative’s success, Lindroth says, is that it’s practically a year-round operation.

After the collaborative’s staff and community center representatives assess how this summer’s programs went, they will begin planning for next year, with a camp leader (an employee of the community center) and a program coach (a member of the collaborative staff) leading the way. The collaborative hires a program dean and a teacher counselor for each site, and they start their preparations in late winter. The rest of the team is filled out by June – reading specialists and 39 high school seniors and college students as reading corps members, behavior dean and specialists, counselors and an operations specialist, who makes sure that all the supplies needed at the site are available each day.

New project-based lessons are developed each winter, so returning campers will not see programming repeated year after year. Also, the programming varies from center to center, depending on participants’ needs and interests.

“The collaborative is a great partner. They’re easy to work with,” says Merv Daugherty, superintendent of the Red Clay Consolidated School District.

Last summer, with the permission of participants’ parents, Red Clay began tracking their performance – where they stood in reading and math skills at the start of the summer, at the conclusion of the program and during the school year.

This year, Red Clay partnered with the collaborative to set up a Tyler’s Camp middle school program at Stanton Middle School, serving 100 students identified by the district as well as middle school youngsters enrolled at Kingswood, West End and Hilltop Lutheran Neighborhood Center.

Next summer, Red Clay would like to add a Tyler’s Camp program for fourth and fifth graders, Daugherty says.

In addition to programs at Salesianum and Stanton, the collaborative operated Tyler’s Camp sessions this summer at McCullough Middle School in the Colonial School District (serving students from McCullough and three Wilmington charter schools – East Side, Great Oaks and Freire), at Sussex Academy of Arts and Science in Georgetown and a pilot for Colonial fourth and fifth graders at Castle Hills.

The strength of the collaborative’s programming has drawn the attention of Dorrell Green, director of the year-old Office of Innovation and Improvement in the state Department of Education.

“The collaborative has done great work with Tyler’s Camp,” he says. “They put summer programs together well, and they connect resources.”

Much of Green’s work in the past year, and most likely a significant portion of it during the coming school year, involves reorganization and new programming for the underperforming schools in the Wilmington portion of the Christina School District. One portion of a Memorandum of Understanding agreed to by the district, the Department of Education and the governor’s office calls for extending the length of both the school day and the school year for Christina’s Wilmington buildings.

The collaborative, through Tyler’s Camp, might be able to provide extended day or extended year services, Green says.

Several providers are offering to develop such programs, and Tyler’s Camp will get consideration, says Rick Gregg, the Christina superintendent.

Also interested in the collaborative’s programming is New Castle County Executive Matt Meyer, whose office provided a $10,000 grant to support Tyler’s Camp this summer. He credits the collaborative with tackling two key issues related to creating healthier and safer communities: inequality among children and summer learning loss.

“They’re doing great work taking assets that already exist, working with programs that already do pretty good work and enhancing them so they do great work,” he says.

“I wish I had something like this when I was growing up,” said Marcus Trott, a Seaford native and Delaware State University graduate student who worked as a behavior specialist at collaborative sites in Seaford and Laurel this summer. “They’re learning and having fun, and we’re giving them behavior modification tools that make it more likely that they will get a good education.”

“This isn’t about finding the right or wrong answer. This is about seeing them grow,” says Chase Darden, the collaborative’s program dean at Kingswood. “You see the results in their confidence and the way they work with each other.”

As for the program itself, Lindroth wants to see it more than double in size over the next two years – ultimately reaching about 7,000 children throughout the state. And that’s not all. Her dream is to secure funding from a major foundation and take the program nationwide.